Ryder Schmidt, a promising young civil engineer working on water resources projects, is involved in hydrologic and hydraulic studies that focus on floodplain and stormwater management. He had proven himself able when it came to technical activities on assigned projects, and he had hopes of moving up in his company. Then he got his chance.

But Rider was quickly overwhelmed by his new job position as team project manager. There is so much to take in and stay on top of when leading a team, ensuring effective communication and coordination between all the architects, engineers, developers, contractors, and clients.

His habits still focused primarily on the technical problems, but now he was having what seemed like the same people problems occurring over and over. As with many people under pressure, his tendency was to blame the other team members, but his boss pointed out that he was responsible for the ultimate success of the project.

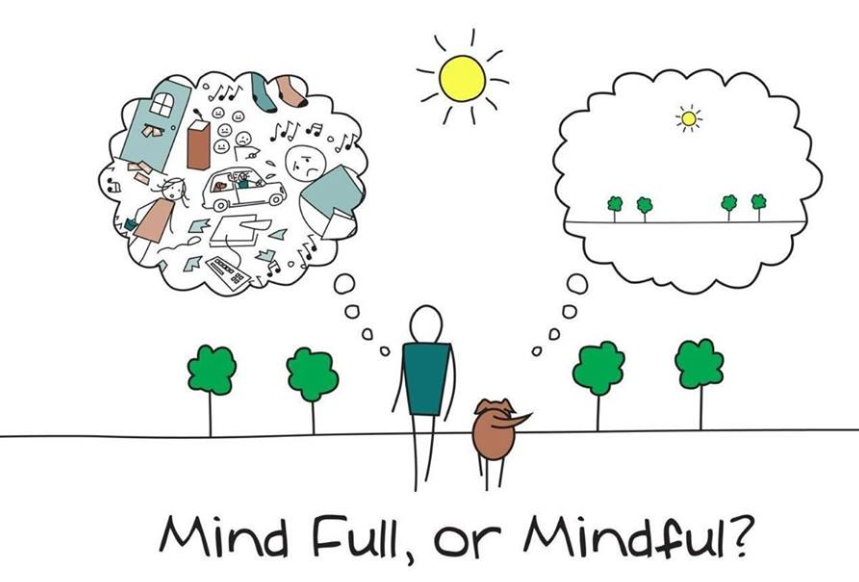

Ryder’s new job was stressing him out. And he knew he needed to focus on people process in addition to the content of his project, but his old work and thought habits were difficult to change.

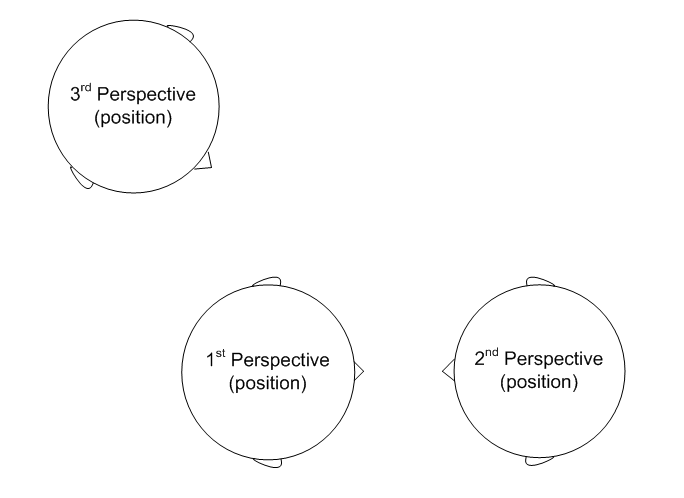

To better manage people, we coached Ryder to become aware of the process of his and his team’s behavioral habits, not just the content of his projects. This can be a tricky distinction for engineers to see and understand because engineers are typically so good at visualizing future creations in their mind that they expect that everybody else should already do things exactly the they imagine they will happen. This is a sort of “mind-reading” and “projection” onto other team members. It is a hazard of being so good at manipulating images in your mind’s eye.

The poor results Ryder was getting came out of the way he habitually used his brain. To choose to do things in a different way, Ryder first had to focus his awareness on how he was producing the consistently poor results. And he had to understand the habitual sequence his brain used to automatically produce those poor results.

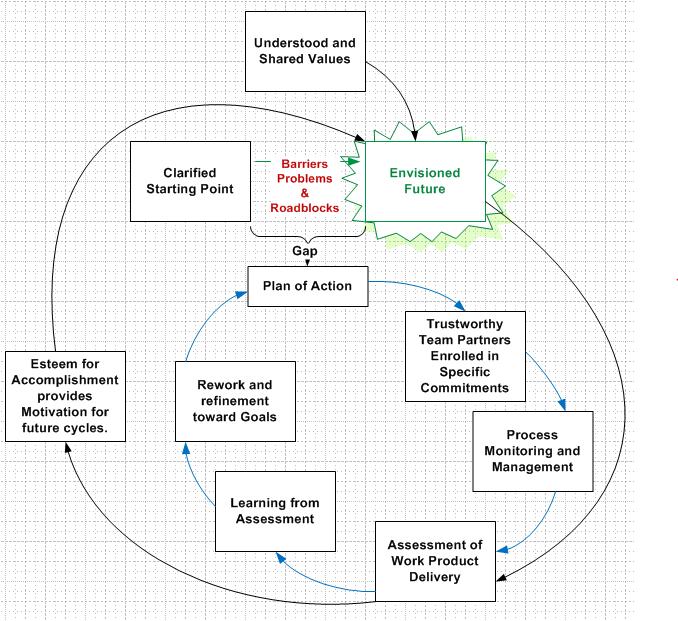

Beginning to learn to recognize and express his own desired objectives in a clear, detailed, and positive fashion, his people were able to collaborate to make sure his vision was in line with their own. This may seem obvious, but in 15 plus years coaching Engineers and Scientists, we’ve learned that it is not as easy as it sounds.

Ryder learned a set of well-formedness conditions for communicating his goals, which allowed him to test his peers and team members’ understanding against his own pictures for success — a sort of failure mode and effects analysis but on the human factors affecting his project. This proved to be incredibly valuable both to him and his team.

Organizing around “well-formed objectives” helped him both communicate more clearly exactly what was expected of his team and check to make sure that all of the key stakeholders shared the same vision and consensus about the steps that the project would entail. This brought out problems for discussion a lot earlier in his projects when they were less critical (and less costly) to deal with.

With a lot of practice Ryder became a master of bringing his projects in on time and within budget. Of course that allowed him to progress in his career. But Ryder said that the biggest advantage came from knowing he could calmly handle any project with minimal stress because everyone was on the same page and working together to make him and his projects a success.

If you think you may be having similar communication problems on your team, you may benefit from learning to apply the well-formedness conditions to the objectives your team has to discuss. To find out more join us for one of our weekly work sessions. We do practice exercises and learn practical skills that help make you a super project manager. Call +1-512-507-5464 for an invitation to join us. We’d love to help you accelerate your career forward to new levels of successful leadership.